In the early days of 2026, as the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) rushed to complete the final preparations for its 14th National Party Congress, a series of unusual developments at the top of the political hierarchy exposed deep and widening cracks within the Party.

On January 6, 2025, an incident drew particular attention when the Ministry of National Defense’s official online portal unexpectedly published—and then swiftly removed—a report announcing that the military had been assigned responsibility for vote counting at the National Party Congress.

Although the information continued to appear on the People’s Army Newspaper, its removal from the Ministry’s official portal inadvertently confirmed the extreme sensitivity of the issue: Who controls the final outcome of the vote?

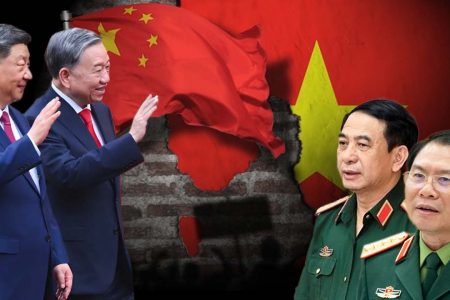

According to international political observers, in Vietnam’s current political context, assigning the military the role of “guarding the ballot box” is far from a routine administrative or security procedure. Rather, it represents a deliberate move by the military faction to assert control over Tô Lâm and the Public Security (police) faction.

In just over a year since Tô Lâm became General Secretary, observers have witnessed an unprecedented rise in the power of the Public Security faction. The expansion of the Ministry of Public Security’s functions and authority, along with the transfer of numerous senior police generals into key positions across the political system, has made Tô Lâm’s power appear all-encompassing.

By taking direct control of the vote-counting process—a critical stage determining the political survival of Central Committee members—the military faction has effectively provided reassurance to those who do not support Tô Lâm, enabling them to cast their ballots with greater confidence.

This move is widely seen as a strategic gambit by the military to restore balance and prevent the police faction from using professional “operational measures” or covert pressure to manipulate votes and intimidate Central Committee members.

It underscores how the “winner-takes-all” tension between the regime’s two most powerful political forces—the military and the police—has never been more openly exposed.

Beyond this power struggle, the “distortion” of political and social life under General Secretary Tô Lâm’s leadership has also fueled growing public resentment.

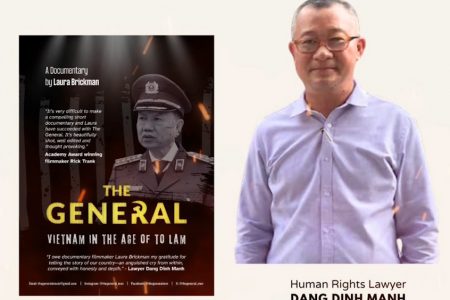

On January 5, 2026, Lê Kiên Thành—the son of late General Secretary Lê Duẩn—broke his silence with a striking post on social media, describing contemporary Vietnamese society as one “where evil and crime appear as casually inevitable.”

Notably, Lê Kiên Thành posed a deeply troubling question about the paradox of development: Why, when the country is no longer as poor as it once was, have people become more brutal and corruption more rampant—even among officials?

His warning struck at what many see as the regime’s Achilles’ heel under Tô Lâm: the absence of democracy within the Party itself.

Lê Kiên Thành argued that when the current General Secretary of the CPV cannot create democratic mechanisms within his own Party, it is impossible to build democracy in society at large—inevitably leading to severe distortions in the economy, culture, and human values.

Meanwhile, the lives of ordinary citizens are increasingly constrained within a “police-state” system that Tô Lâm is rapidly constructing.

In short, from the military’s intervention in the vote-counting process to Lê Kiên Thành’s dissenting voice, it has become clear that the 14th Party Congress is not merely a personnel transition, but a fateful crossroads.

The military’s last-minute intervention may well be the final barrier preventing the absolute monopolization of power by the Public Security faction under Tô Lâm’s leadership.

Trà My – Thoibao.de